Making No-Frills on Morality and Music Piracy

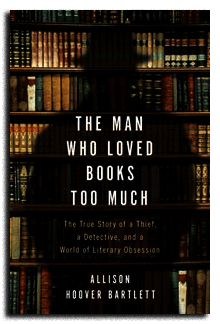

(Cover) The Man Who Loved Books Too Much (Cit. Allisonhooverbarlett.com)

Gilkey said that he didn’t like to spend his own money on books and that it wasn’t fair that he didn’t have enough money to afford all the rare books he wanted. To Gilkey, fairness seemed like a synonym for satisfaction. If he is satisfied, all is deemed fair. If not, it isn’t.

“I have a degree in economics.” he said, in an effort to explain his compulsion to steal.

“I figure, the more books I get for free, if I need to sell them, I get 100% profit.”

-John Charles Gilkey (from The Man Who Loved Books Too Much, by Allison Hoover Bartlett)

****************************

Why did I start this piece out with an excerpt from a book? This wasn’t exactly an intended decision. In truth, I was simply going about my evening, after having done a bunch of work and necessary errands, just starting this new novel that I picked up from the library this afternoon. It’s a mystery of sorts and being on the mystery/suspense/slightly dangerous book kick I’ve been on lately, why not give it a try?

Well, not an hour or so into reading, I find this passage and immediately stop to write it down because I had to think about it. The very first thing that came to my mind after that whole exchange finished was,

“Wait a minute…the music industry!”

Yes, I know, a lot of the music business devoted portion of the internet just got finished loudly pounding away at their keyboards responding to one, two or all sides of that whole Emily White/David Lowery/Emily White #2 triangle. Still, my mind can’t seem to turn away the very fundamental but nonetheless valid point that came out of Bartlett’s writing.

Here we have a man who validates his stealing of a borrowable/buyable commodity with:

- A lack of money

and/or

- A lack of adequate motivation to properly spend money

Scenarios like Gilkey’s drive me to question why, the act of downloading music is continually downplayed by so many, from being called what it is: Theft. After all, words can be re-typed and books can be re-printed. Yet, if you swipe literature, it’s theft. Period. This isn’t an inquiry about “severity of theft.” (e.g. A child steals one pack of gum from a candy shop, their parent covers the cost, later scolding the child for doing something wrong -namely stealing.)

I’m aware the excerpt I posted, and the scenario of the book in general, deals with a man who is jailed for large scale, repeated theft of rare works and that you might come back to me and say,

“Hate to break it to you, but if so-and-so ‘steals’ a digital copy of Adele‘s “21,” that’s hardly rare and most people aren’t hopping online to try and download some rare, limited edition release of a CD; not to mention that kind of genuinely rare stuff doesn’t tend to get uploaded in the first place.”

Believe me, I’m not trying to make that direct of a parallel. Chances are you don’t get years and years of hard time if you are busted on one album, let alone one song downloaded. It’s more Gilkey’s mentality that gets the fuels of discussion going on this one. To give you a key detail on the character profile of this main figure in Bartlett’s book, Gilkey loves books. …To the point of “bibliomania,” as Bartlett describes him.

Again, the character’s level of emotional investment toward literature doesn’t equate to most individuals’ emotional investments in music but his level of seriousness and remorselessness in what he says, combined with an aligned sense of entitlement and/or experiencing unjust deprivation is absolutely something I feel can be draped on top of many a music “consumer” of today. How many times do people who ‘like music a lot,’ just want to reiterate why this fight toward piracy is so extreme or excessive or even unnecessary and shut down the discussion of why it’s wrong altogether? If it’s uncomfortable to talk about, it’s most likely because the person knows what they’re doing and doesn’t like to talk about it or because the whole problem/argument is just too big and annoying to talk about, let alone solve, so the solution is to just talk about something else.

The only thing I am asking, is:

Why isn’t music given the same kind of backing as any other manifested product, where, if you take it and it’s not yours and you don’t pay for it, you have stolen something. For the young child that takes that one pack of gum, sure, the shop they took it from won’t have to file for bankruptcy if the gum isn’t paid for but if it wasn’t the wrong thing to do, then why have parents punished their kids in the past for this exact action? It’s a concept that (most) are taught as kids, and I don’t think a concept suddenly changes just because you’re older. Can we at least concede that this is a sensible line of logic and not follow these concessions with a bunch of self-constructed justifiers that start with “but?”

As a music loving public, let’s stop wishing and justifying with, “if things were different,” or “he/she was raised around XYZ social norms” or even, “this is just the way things are now.” I’ve never seen another industry get so backseat driven by the people who want its commodities. The consumer gets to say, “I’ve been getting what I want this way for this long. It’s the industry’s fault. I’m the one with the money and the buying power, so if they just delivered in X-ideal way, at X-ideal time, I would be happy.Businesses might need customers to survive but, if you want to get extreme: If music suddenly made no money because every person in the world decided not to buy or participate in the market anymore, musicians and artists, with their creative and passionate souls, would still have the special thing that makes them musicians and artists in the first place. They could still create, take pride in, and enjoy what they do because it’s who they are. Meanwhile, the listener would simply be without it. Furthermore, if you think my postulating these ideas is far-reaching and non-realistic, well, had no one ever tried to make waves in the past because a situation seemed “too big” or “too crazy” to ever change, society would be a heck of a lot different wouldn’t it?

Think about it. Intensely, for a moment, think about it.

One Response to “Making No-Frills on Morality and Music Piracy”

While I tend to agree that music is a product, it is now largely being viewed as a service, and given the sheer volume of options we have as a consumer base to acquire music digitally, whether on a permanent basis through iTunes, Amazon, or artist’s websites, or as a streaming service such as Grooveshark, Pandora, or LastFM, we have moved away from supporting the record industry as a whole through the traditional brick and mortar store.

I personally still purchase albums on CD, though not as frequently as I once did that is for me, a matter of my general dissatisfaction with the resultant quality of the product and is also influenced by the availability of these streaming services that provide me the music I want with little effort, and little/no monetary commitment.

Artists such as Jonathan Coulton, MC Frontalot, MC Lars, The Offspring, Nine Inch Nails, and many others have spoken out in favor of file sharing, some releasing songs or whole albums for free through their websites and others writing songs lambasting the record industry for their slow to change nature.

Generally what we’re seeing at this point is that a song is a product, but music is a service. Most artists are moving to make more of their money from concerts and from merchandising. They still press CDs, but the allure isn’t just the music now. Musicians have taken to selling the art, the prestige of owning the album as much as its contents.

I don’t think it’s unfair to say that many pop artists releasing albums with only three or four quality tracks and under 45 minutes of running time helped to spur the growth of piracy, and to help justify it to many early adopters, not believing that the artist has “earned” the money helps justify people stealing the music. After being burned by an artist on an album or two, I most certainly stream the entire next album before deciding to buy it now.