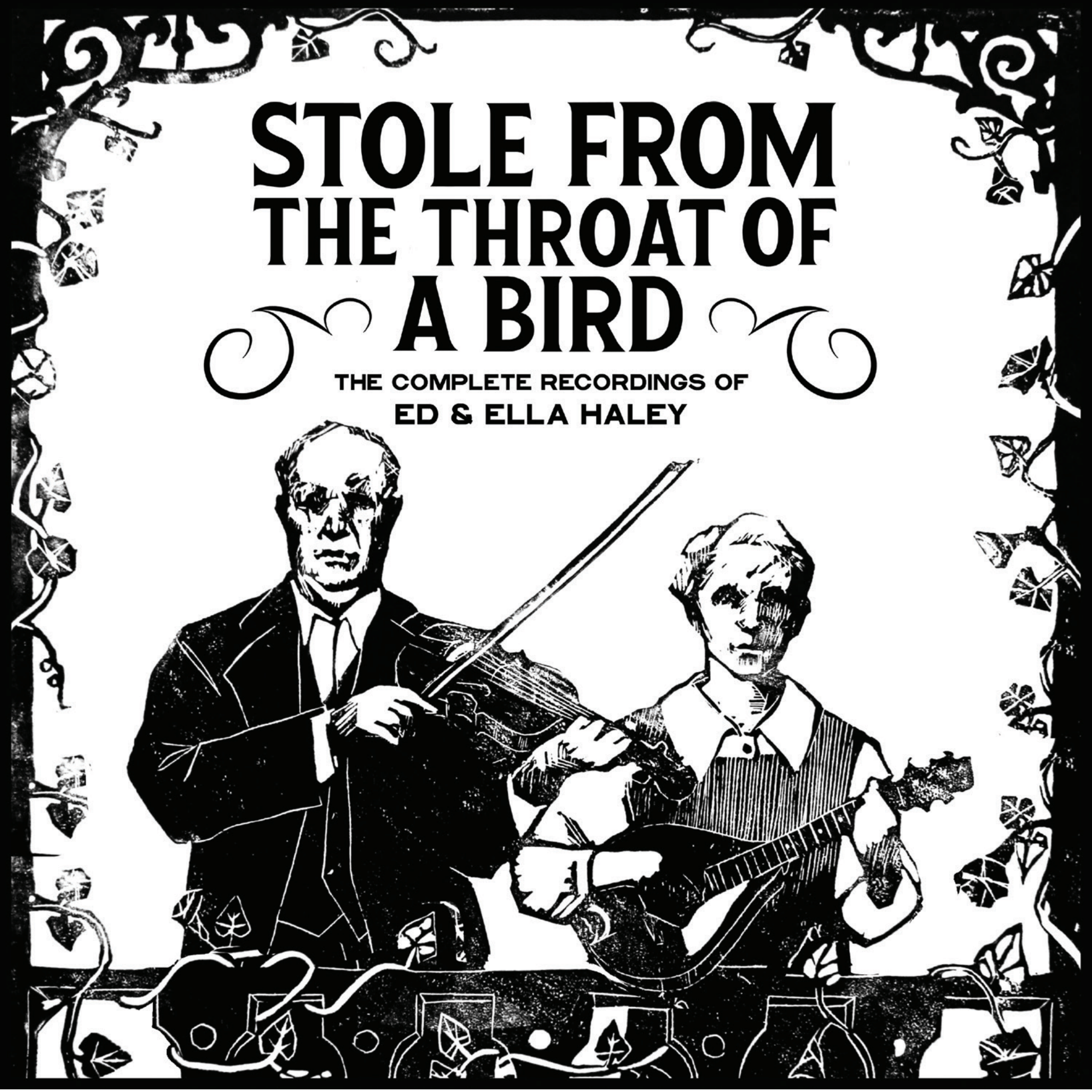

Restoring the music of Ed and Ella Haley that Spring Fed Records “Stole from the Throat of a Bird”

Image design credit: Heather Moulder.

They say hindsight is 20/20 and usually when it hits, the accompanying realization feels so incredibly obvious that it’s hard to understand how details end up getting missed the first time around. In the case of Stole from the Throat of a Bird: The Complete Recordings of Ed and Ella Haley the completist boxed set recently completed and unveiled by Grammy-winning label Spring Fed Records back in August of this year, the team of John Fabke, Greg Reisch, and Martin Fisher knew exactly what kind of details were “missing” when they decided to shoot for the musical moon. The small but mighty team with the traditional, old-time music-focused label run by The Center for Popular Music at Middle Tennessee State University, aimed to restore and compile all the recordings of Appalachian fiddler Ed Haley and his wife, Martha Ella Trumbo – better known as Ella Haley. While quantity on its own – the set totals seven discs and over 150 tracks – is an easily appreciable metric, the folks at Spring Fed had another handful of challenging aspects to contend with: musical medium, audio quality, and the physical act of restoring the audio carved into discs far less durable and permanent than the ever-enduring vinyl.

Never mind the absolute mountains of research, reporting, interviewing, conversing, transcribing, writing, designing, printing, copying, and packing that went into this project, all of which goes well outside the scope of the Haley’s music. The work that took place over six year tumbled into compilations of scrupulous historical notes, artist insights, and photographs, familial accounts, and much more, which was assembled into 103 pages of liner notes and other supplemental materials. The recordings and music recovery mission alone are undertakings which were at the mercy of no one’s timeline except that of Martin’s Fisher. His patience, resourcefulness, and arsenal of surprisingly low tech machinery served as the main methods of help on the route to recovering these recordings. Fisher, an expert audio engineer and the Curator of Recorded Media with Spring Fed, faced and embraced the gargantuan task of extracting sound that was on the verge of disappearing without recovery, using ideas and approaches that required as much small, meticulous, and painstaking accuracy as the project’s historical aspects required large wells of stamina and broad reaching organization of detail-heavy information. If the mere thought of manually removing every speck of dust out of a many-decades-old vinyl sounds unfathomable enough, imagine having to navigate the delicacy of discs made from paper, and retracing the lines of sounds long of the past, with motor-less tools bearing points finer than the fanciest ball point pen.

Fisher, who loves what he does and who saw more strategy than struggle as he undertook the Haley project, spoke about the nuances of not just recovering the Haley family’s music but in the work of restoration as a whole and what makes it a worthwhile labor of love.

Spring Fed RecordsCurator of Recorded Media, Martin Fisher | Image courtesy of Martin Fisher

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How would you describe what you do as an audio restorationist?

Martin Fisher: “Well, I hate to call myself a restorationist is but…that’s kind of what I am. [The work] is more of just bringing [the music] up to the standard of sounding like it was, kind of when it was new, but not trying to like overdo things. So what I tried to do, is go in and do as little as I possibly can to the actual audio itself because I want the full vocal, I mean, the full range to be there.

And, a lot of the reissues that are put out nowadays –– not all of them, and there’s some real good ones –– there’s also some that have been like, ‘Who’s doing this stuff?’ You know, a quarter of the program content is gone, along with just about either a good bit of, or most of the noise. But I would rather hear what was there than, you know, miss out on something. And so that’s sort of the where I’m coming from.”

What does a typical analysis look like for you when you’re presented with a new, or in this case old, audio medium that’s in need of revitalizing or outright repair?

Fisher: Evaluating [the medium] depends on what it is. Let’s use records since that’s what we’re dealing with, with the Ed Haley material. These [recordings] are [made of] either aluminum –– they’re either bare embossed aluminum in one case, that would be two cuts –– or they are aluminum or steel coated with a lacquer substance that’s actually a natural cellulose lacquer. A lot of times it’s called acetate because these things were equated with acetate pressings that went to radio stations. Back in the probably the 1930s is what I’m remembering. So [the recordings] are called acetates but they’re really natural cellulose lacquer for the most part, over either an aluminum, glass, steel, cardboard, or fiberboard base like a pasteboard bass. And a lot of times, the the lacquer itself, which the groove is cut into, in the case of the lacquer recordings, and not bare aluminum is will shrink at a different rate, like a coefficient of expansion and contraction, then the base. So you’ve got, you’ve got a lot of cracking that occurs. The stuff is very soft, actually. It’s more durable than I think some folks might realize, and pliable, but it’s very soft and it’s very easy to damage with the first play. Matter of fact, the first play sometimes will burnish the groove and on the first go around, and subsequent plays are usually not that that much worse, but you have to watch out what you actually put in that groove.

How did the Haley recordings fair in this regard? What, if anything did you have to adapt in your process, in order to give the recordings their best chance at quality recovery?

Fisher: There’s nothing really special that I did, but what you encounter some of these things, and…actually, this [one] particular disc, and a lot them were on cardboard or fiber-based discs, have a tendency to warp and other things. And so this one was what we call ‘alligatored’ real bad. In other words, the lacquer had cracked in real fine little pieces on the surface. And I actually wet play these things to clean them, and also to transfer them it’s a little bit [of a] dicey process and you have to watch what you’re doing and when that happens with sometimes this lacquer that’s cracked, even makes it worse because it wants to curl a little bit where the cracks are. And it was already bad enough but, it would have sounded horrible. If I had tried to transfer it like it was without any cleaning.

And then the disc itself was unevenly warped in a number of ways. And so what I did was, I put it on another single-sided 78 which was pretty much flat, and then I set this up cut a hole in the bottom of [a] Pringles can for the spindle. And I probably actually didn’t even need it because I raised the record up above the spindle in order to center it properly. And then I filled [the can] because I needed some weight to actually hold the center area of the disc down flat. I filled it with nuts and bolts and everything I could find. And again, the record itself is raised completely above the spindle on the on the turntable so I could manipulate it any way I wanted to as far as centering the thing. And then I use the Pringles can as a large footprint to actually hold the center of the disc down.

Set up for transfer of audio using a Pringles can. | Photo courtesy of Martin Fisher

How do you discern what is “less than good” due to age, but perhaps salvageable, and what was beyond recovery? Are there any particular hallmarks, like appearance of a warped vinyl per se, that you watch for?

Fisher: When people come to me, and it’s usually Mom and Pop you know? It’s usually not a project like [the Haleys], my gosh, this is just a massive thing really. They come to me with like, one or two of these type of recordings and they say, ‘You know, I don’t even know if it’s salvageable. Is it?’ And it’s exactly the same type of disc as that Haley disk with the Pringles can. I mean, exactly the same type of blank and everything. But the surface has literally peeled off and it had it had all sorts of this plant life growing underneath the lacquer and over the top of it. And so I tell them, ‘You know, are you really concerned about the media itself? Because I can get something out of it. And the more I do with it, the better I can get a result we will have. But the original artifact itself might not come to you in exactly the same shape as it lift your hands in. In other words, I might do a little physical damage in the long run. But you know, if you wait, the longer you wait, the more damage is going to be done. And if I slap this thing on a turntable and try to track it with a stylus I might get something out of it. But if you let me do my methods, even though they might end up in the long run maybe shortening the aesthetic looks of the thing, I can get a much better result.’ And I do.

And I’ll leave it with them and most of the time [they say], ‘Just recover the stuff.’ And I’m like, ‘Okay, that’s what I’m looking for.’ And so, if it was an 1898 cylinder or something like that, I would be more concerned. But this is an object that is degrading, almost daily, just sitting on the shelf. I’ve seen [recordings] do that too. So I’ll tell folks that and what I generally do is, I will try anything once –– as long as I have their permission. I will try anything within reason you know, and being careful. I hate to degrade an object more. But I’ve done some stuff, I think without bragging or anything, I’m not trying to do that. But I’ve really gone above and beyond on a lot of things because I’m kind of a perfectionist and you know, I don’t want to put my name on something that I don’t consider a good job. It is a challenge. And it’s one of the things that makes what I do kind of fun.

Off-center disc played using an unsteady tone instead of music to illustrate effect of off-center playing

How has working on the restoration of the Haley family discography changed or affected the way you view and feel about the Haley’s music?

Fisher: It’s taught me that’s take a step back and try to de-stress. I mean really, but as far as methodology goes, I’ve learned a lot doing this. I mean, I’ve learned a heck of a lot doing this project on my own. But the main thing about this project was that it was big. It’s been a long time coming and I mean, I asked for it. I wanted to check the chance that these things because I’d heard them and they sounded pretty rough. I thought I could do a little better job.

And it’s not that I know much more but you know, the methods have changed, the methodology, and other people and I have different ways of doing things. And when [the audio on these recordings] were transferred before, it was a real hurry-up process because I understand that these things went to the Library of Congress. They didn’t have them for long. They just played the darn things. And then worked on them –– done filtering from there. But they didn’t have the the resources that we have today. And they didn’t have the time, which was the one of the main resources –– not the only one but the only the other one that really made a difference.

And I can say everybody has different methodologies. I always say that when I talk to people, you can train a monkey to do anything that I do. The thing you can’t do, is make the monkey care. And I think there’s lots of people out here who are worried about quantity more than quality. And I’m not saying this to–I know I sound conceited but I don’t mean to. I just really care about what I do. And, like you I’m sure, we want to do the best that we can in our own eyes, you know, because we don’t attach our names to something we don’t want, or that we wouldn’t like ourselves. And I’m sure there’s room for tons of room for improvement over even what’s going to come out [through this project] but, at what cost, you know? And I would rather have everything there than missing something and have it sound a little better to somebody’s ears, although I’ve had to take that [aspect] into account. I know that people are expecting great things with this project. I mean, I have to deliver. I want to deliver.

Stole from the Throat of a Bird is available now via Spring Fed Records.

Stream the music on Spotify.

Buy the complete boxset of the collection from The Center for Popular Music.

Learn more about the mission and work of the Center for Popular Music at Middle Tennessee State University (one of the world’s oldest and largest research centers devoted to the study of American folk and popular music,) at its official website.

Stay connected with Spring Fed Records through its official website and these social mean platforms:

Facebook

Twitter (@SpringFedMusic)

Instagram

YouTube

SoundCloud

Leave a Reply