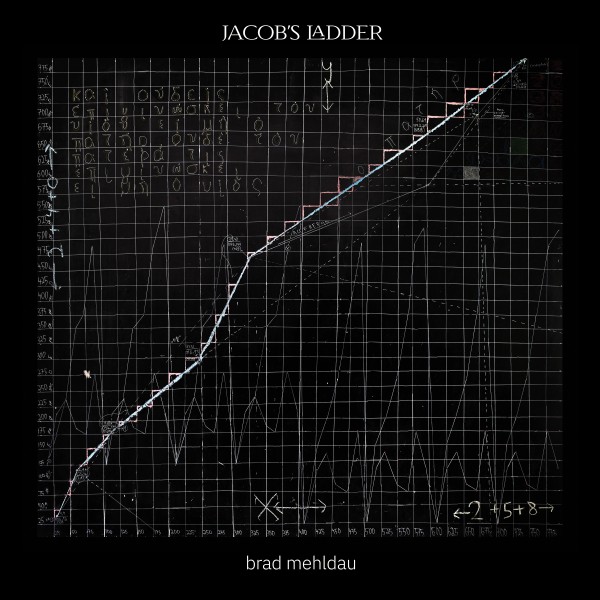

Brad Mehldau lifts his music to spiritual heights with “Jacob’s Ladder”

Image courtesy of Nonesuch Records

The announcement that Brad Mehldau’s newest album, Jacob’s Ladder, was going put the jazz composer and pianist’s relationships with spirituality, progressive rock, and God at the forefront, might seem mildly shocking to some when heard as news on its own. However, with just slightly closer inspection, one will observe that Mehldau’s two most recent releases as leader or co-leader — 2019 Grammy-winning album Finding Gabriel, and Suite: April 2020 — offer their own conceptual and inspirational ties to the ethereal and the religious. The former focused on the nature of everyday graces, struggles, and routine or ritual during lockdown in 2020 and the latter was built from a core based in the lessons of Biblical scripture, which happened to run uncomfortably parallel with the unstable dynamic of fake news and objective truth happening in global society leading up to the time of the album’s writing. Seen from this fuller context, the conceptual focus of Jacob’s Ladder makes for a logical expansion of the spiritual and theological realms Mehldau has already cared to provide reflection upon through his previous works

Brad Mehldau | Photo credit: Sofie Knijff

What makes Jacob’s Ladder stand out nicely from its two predecessors, is the fact that Mehldau has chosen to turn the lens back upon himself. Suite: April 2020 did come from a place of reflection on Mehldau’s day-to-day life and real experiences. Yet, that vantage point presented a broader, more externally observant angle than one of self-driven introspection and a processing of the wholly personal, internal, and self-contained. Though Mehldau has broached the subject of his spirituality and its relation to major global religion before (he expounds on his Gnostic view, with great detail and open mindedness, in a 2010 essay written for The Scope Magazine titled, “Coltrane, Jimi Hendrix, Beethoven and God,”) Jacob’s Ladder serves as a reinforcing display of Mehldau’s willingness to accept a wide swath of theological grey.

Gnosticism, as Mehldau had said in his essay, “mak[es] a pessimistic – and potentially defeatist – claim: God has moved away from us now, and is too far to reach. God cannot hear us, and we cannot hear God; the distance is too wide.” Nevertheless, Mehldau’s embrace of God, at the very least within the context of Jacob’s Ladder, if not a larger portion of Mehldau’s life, is presented as notably more hopeful and driven by the potential for redemptive connection than the futile nature of classic Gnosticism implies. More than 10 years after that in-depth essay, Mehldau embraces room for spiritual repair, and affirms his appreciation of grey optimism, with the album’s titular object positioned as a symbol for achieving positive reconnection rather than fixed and dismissive loss. He says in the liner notes of the album, “We are born close to God, and as we mature, we invariably move further and further away from Him on account of our ego. Jacob’s Ladder begins at that place closer to God with the voice of child, and then moves into the world of action…He sets a ladder before us though, like in Jacob’s dream, and we climb towards him, to find reconciliation with ourselves, to stitch up all those worldly wounds and finally heal. The record ends with my vision of heaven—once again as a child, His child, in eternal grace, in ecstasy.”

The trajectory of Jacob’s Ladder takes the listener through this fall from grace that Mehldau posits and its manifestation in his compositions and unique arrangements is nothing short of beautiful and nuanced. The opening track, “maybe as his skies are wide,” which both in title and in the song itself samples a section of Rush’s “Tom Sawyer,” also on Jacob’s Ladder, sets a bold tone of innocence and pure intrigue by way of delicate treble vocals performed by Luca van den Bossche. The ever-so-slight shakiness to van den Bossche’s vocal timbre, combined with the high register, imparts a feeling of newness, of something just establishing itself, like the time when a newborn first gains its spatial awareness, or balance, or footing. Mehldau’s integration of equally delicate instrumental parts like glockenspiel, high octave twinkling piano, and drier toned sampling and drumming, enhances the ambiance of the music, while surrounding the repeated central message with a sense of transformative change, much the same way Mehldau’s scenario posits that humans begin in one place of spiritual connection and, in our increased awareness of and pursuit of self, simultaneously change and begin to lose that fundamental message amidst everything else that steals one’s focus away. And yet, by the end of the track, the piece has once again reduced itself to the purity of its opening message, with no distractions, and in this way, the opening track is almost like a microcosm of the album’s overall trajectory.

The presence of progressive rock throughout Jacob’s Ladder is serves as the crux of the musical parallel to the spiritual trajectory of the album. Listeners are able to witness through Mehldau’s varying degrees of interpretation on the album’s several cover tracks, is where and how much elements of his jazz artistry blend alongside the defined qualities of 70s progressive and art rock. Knowing that Mehldau grew up with the songs and sounds of bands like Rush; Emerson, Lake, and Palmer; and Gentle Giant among others, Jacob’s Ladder shows the different sides of Mehldau’s musical inclinations ebbing and flowing like the tides – easily observable and discernible from a distance but in reality, subtly changing and shifting with fluidity each time. It’s a gradual, not necessarily cleanly linear map of sonic changes. The album moves from the dramatic and aggressively progressive rock-styled original track, “Herr und Knecht” (The title nods to a philosophical premise, Herrschaft und Knechtschaft, by Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, involving an encounter between two self-conscious beings,) to the classical-style angelic musicality of “Glam Perfume.” The latter track glows with classical form, boasting the poise of arpeggiating harp melodies, gentle syllabic “ahh” vocals, and a seemingly more classically-traditional piano melody.

Then a few tracks later, the classical and the progressive collide head-on, when Mehldau’s original “Double Fugue,” the third part of his “Cogs in Cogs” suite which encompasses the Gentle Giant track of the same name, unfurls a decidedly Baroque-style composition, played entirely using a rounded tone Moog (this subs in for an organ’s softer more flute-like tone rather nicely) and an emulator synthesizer. The tones harken to the prog-minded ear while the melody and harmonizing chords are all traditional classical. This extreme swing toward such an early form of classical music almost nods back to the starting theme and thoughts around God and our state of being as mortal humans, as during the Baroque and many other eras of classical writing, music was designated for explicitly non-secular purposes. The ornateness of certain pieces was intended as a method of glorification and exoneration of God from the place of humans as fallen beings.

Mehldau, as the master of the project, lets listeners know where the journey will conclude – back in a state of connected grace. However, the clarity with which he moves in and out of the musics of his past, present and presumably some form of his future, is left a little messy and strcuturally unpredictable (this is with regard to intended stylistic presentation of his arrangements, not compositional finesse) when examined up close. Whether reflected upon in the macro form of the track list, or much more closely among the individual musical elements of any single track, the music constantly reminds the listener there is a duality going on, a separation and an desire of seamless reunification. It’s only at the very end, when Luca van den Bossche’s vocals return – and be mindful of the fact that this only occurs after a wide breath of Mehldau’s jazz writing played on a grand piano; jangle style acoustic guitar; beep-style Moog; disciplined and syncopated harp; smooth and confident vocals by Cécile McLorin Salvant; crackling snare, Fender Rhodes, and much more, rain down a shower of sound in Mehldau’s version of “Heaven.” Instruments one might have expected to take a certain role in the sound stage of the arrangement or in the stylistic setup of the song’s central melodies and harmonies – the harp’s shift to a notably static and more rhythmically-driven role over its naturally flowing and symphonic style qualities, comes to mind – give a final of what can manifest when familiar elements are introduced from a different place and with a different objective.

It’s an absolutely grand and fitting finale both for the purposes of showing us how Mehldau finds a way to balance his artistic self and how the people in Mehldau’s explanation start in one place and can ultimately end up back there, but not necessarily in the way that the listener may think they want or expect. The important thing, by the arrival of the last note, is that the music was able to get there and unveil that original place, only now more enhanced with all the life experience that was accrued along the way.

Jacob’s Ladder is out now via Nonesuch Records.

Find it through Bandcamp iTunes, Amazon, and streaming on Spotify.

Keep up with Brad Mehldau through his official website and these social media outlets:

Facebook

Twitter (@bradmehldau)

Instagram

Bandcamp

Spotify

SoundCloud

Leave a Reply