Weave Me a Web of: Violin Strings? (Not a Bunch of Lies!)

It’s always fascinating for me to find out about and follow up on news of advancements in the construction, use and quality of the violin. As an instrument that requires a meticulous amount of work to build and lends itself to an even more intense level of individual customization, violins, at least to me, are like the snowflakes of the instrument world. No single one is alike. Granted, one could potentially say that about any handcrafted instrument but some materials inherent to the violin –like wood remind me so much of other things that change with age and time. Like a good bottle of wine versus a bad one. From year to year, grapes from the same vineyard may produce a near perfect, balanced taste on the palate and others, a terribly bitter and unrefined one, simply because of how the weather and affected soil were that year.

Sorry, I know this isn’t a vintage wine blog.

Wood definitely can be cared for and affected over time and when used for something intended to create sound, every different type results in a different tone color. Add different bow weights and hairs and the types of strings one uses and there’s no wonder finding the ‘instrument for you’ is like shopping for just the right car. It’s probably where that whole aggressive philosophy of “no one touches my instrument but me” came from. After all, this things you customize to fit your needs is unique to you as a player. Everything is how it best works for you while you play. (And oh yeah, it’s probably insanely expensive to boot.)

Well, for the latter in customizable stuff I mentioned above, creative advancements have indeed been explored. Japan, whose string players have been thriving on the Suzuki Method since the mid 20th century, thanks to Shin’ichi Suzuki, has turned out another potential long term innovation in violin string construction. Shigeyoshi Osaki, a “professor of polymer chemistry at Nara Medical University” (Cit. HERE) has tinkered with a new material for violin strings. While many early strings used to be made from Catgut, (No, not felines, and no, not guts in the crude way I’m sure you’re thinking.) other types were eventually developed that moved away from organic material. Steel-core and synthetic-core are common today.

What Osaki has done in conjunction with this knowledge of polymer chemistry and his own love for the violin, is developed spider silk strings. Upon first hearing, this may sound questionable, but the concept is rather ingenious. Osaki explained to the BBC that in studying the fiber composition and tensile stength of the silk strands he found they,

“…withstood less tension before breaking than a traditional but rarely used gut string, but more than an aluminum-coated, nylon core string.” (Cit. HERE)

Spider webs do tend to take a lot of damage that’s dished out to them by way of wind, rain, snow, even young children that try to just blow the webs away. These structures don’t tend to just fall apart at the first moment of slight disruption, short of taking a stick and hitting them directly. So I suppose this feat of durability fits well with the kind of tension and stress needed to be string material.

Of course, quality and quantity are two very different things.

Osaki ventured to first make a set from silk of spiders from the Nephilia Maculata species, which comes from the genus Nephilia and makes the Maculata a type of Orb-weaver. The defining characteristic for Osaki in choosing this species was their innate ability to weave elaborate webs, making their silk ideal for construction experimentation; proving to be necessarily durable. The quantitative quandary with making the strings is the need for so many. 300 females provided the adequate amount for a full 4 string set to the first violin. 300 spiders. I am going to be open about this and say while I am excited by this study and prospect, you would not catch me in a room with 300 spiders ever. I will thank them for contributing to the beauty of music, but from a considerable distance.

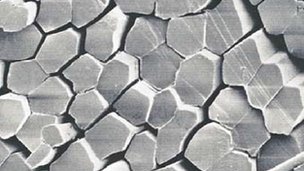

Aside from the string strength, the other notable difference in what the silk managed to achieve, is a lack of space. What I mean by that, is space on a molecular level between the individual strands groups together to formed the individual strings. Lost yet? Here’s how it goes:

1) 300 spiders make lots of silk. (3,000 to 5,000 strands approximately)

2) These thousands of strands are twisted together going in one uniform direction, making one bundle.

3) Each single violin string is made from three bundles, which are twisted in the opposite direction that the strands were twisted in (e.g. clockwise for the strands, counter-clockwise for the bundles.)

If we do a little basic math, that’s,

3,000 to 5,000 x

3 bundles x

4 strings

—————–

36,000 to 60,000 strands of silk per complete string set.

When Osaki does the twisting of the strands to create the bundles, molecular viewing for the pieces showed a drastic reduction in gaps between the fibers to what he describes as “no space.” (Cit. HERE)

The significance? “It made the strings stronger;” (Cit. HERE) further enhancing the inherently tough material.

|

| The cross-section of one silk bundle as viewed under an electron microscope at 70 millionths of a meter wide. (Cit. HERE) |

The strings aren’t widely available yet, as their use and longer term viability are still being examined but some players have given the sets test runs and it is noted in the Journal of Physical Review Letters‘ introduction on the work, to have a “soft and profound timbre.” Further explanation of Osaki’s studies will be released in an upcoming full volume. If these strings ever catch on in mass, maybe I’ll give them a run for myself. Any time you get to experience a difference tone, you could find something that appeals to you and expands your tastes as a musician.

I decided not to include a photo of the ‘spider of the day,’ should any of you readers out there find them unpleasant to look at or just have straight up Arachnaphobia. Something described by the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles as being “the size of a chocolate chip cookie” doesn’t personally thrill me; particularly because I like chocolate chip cookies.

Leave a Reply